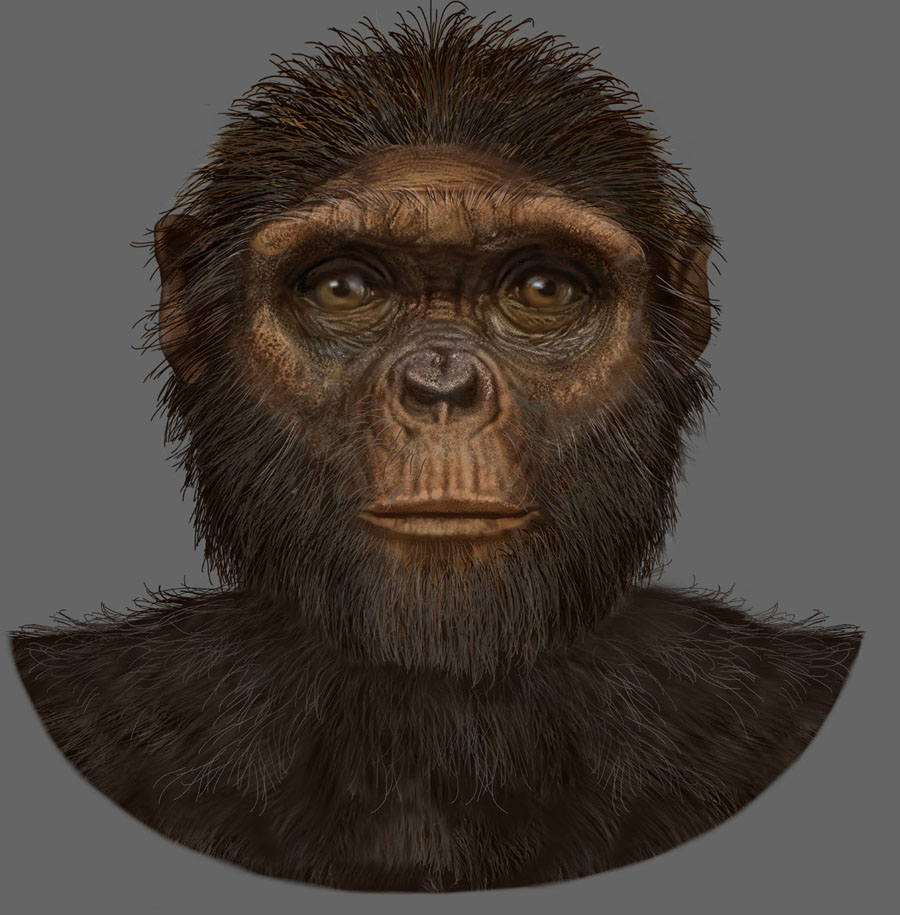

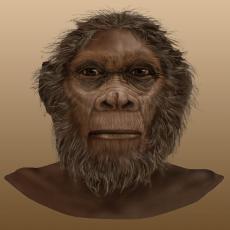

Sahelanthropus tchadensis

Sahelanthropus tchadensis is one of the oldest known species in the human family tree. This species lived sometime between 7 and 6 million years ago in West-Central Africa (Chad). Walking upright may have helped this species survive in diverse habitats, including forests and grasslands. Although we have only cranial material from Sahelanthropus, studies so far show this species had a combination of ape-like and human-like features. Ape-like features included a small brain, sloping face, very prominent browridges, and elongated skull. Human-like features included small canine teeth, a short middle part of the face, and a spinal cord opening underneath the skull instead of towards the back as seen in non-bipedal apes.

Orrorin tugenensis

Living around 6 million years ago, Orrorin tugenensis is the one of the oldest early humans on our family tree. Individuals of this species were approximately the size of a chimpanzee and had small teeth with thick enamel, similar to modern humans. The most important fossil of this species is an upper femur, showing evidence of bone buildup typical of a biped - so Orrorin tugenensis individuals climbed trees but also probably walked upright with two legs on the ground.

Ardipithecus kadabba

Ardipithecus kadabba was bipedal (walked upright), probably similar in body and brain size to a modern chimpanzee, and had canines that resemble those in later hominins but that still project beyond the tooth row. This early human species is only known in the fossil record by a few post-cranial bones and sets of teeth. One bone from the large toe has a broad, robust appearance, suggesting its use in bipedal push-off.

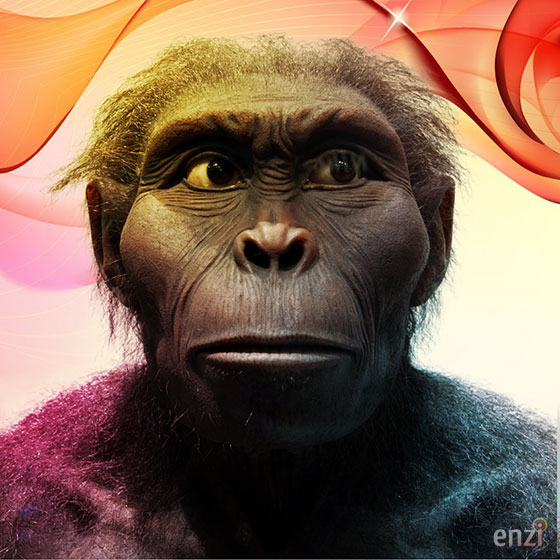

Ardipithecus ramidus

Ardipithecus ramidus was first reported in 1994; in 2009, scientists announced a partial skeleton, nicknamed ‘Ardi’. The foot bones in this skeleton indicate a divergent large toe combined with a rigid foot – it's still unclear what this means concerning bipedal behavior. The pelvis, reconstructed from a crushed specimen, is said to show adaptations that combine tree-climbing and bipedal activity. The discoverers argue that the ‘Ardi’ skeleton reflects a human-African ape common ancestor that was not chimpanzee-like. A good sample of canine teeth of this species indicates very little difference in size between males and females in this species.

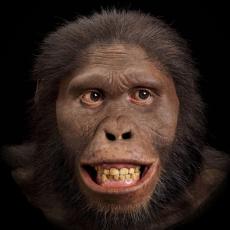

Australopithecus anamensis

Australopithecus anamensis has a combination of traits found in both apes and humans. The upper end of the tibia (shin bone) shows an expanded area of bone and a human-like orientation of the ankle joint, indicative of regular bipedal walking (support of body weight on one leg at the time). Long forearms and features of the wrist bones suggest these individuals probably climbed trees as well.

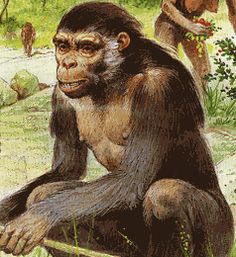

Australopithecus afarensis

Australopithecus afarensis is one of the longest-lived and best-known early human species—paleoanthropologists have uncovered remains from more than 300 individuals! Found between 3.85 and 2.95 million years ago in Eastern Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania), this species survived for more than 900,000 years, which is over four times as long as our own species has been around. It is best known from the sites of Hadar, Ethiopia (‘Lucy’, AL 288-1 and the 'First Family', AL 333); Dikika, Ethiopia (Dikika ‘child’ skeleton); and Laetoli (fossils of this species plus the oldest documented bipedal footprint trails).

Kenyanthropus platyops

Very little is known about Kenyanthropus platyops—a flat-faced, small-brained, bipedal species living about 3.5 million years ago in Kenya. Kenyanthropus inhabited Africa at the same time as Lucy’s species Australopithecus afarensis, and could represent a closer branch to modern humans than Lucy’s on the evolutionary tree. Before the discovery of the only known skull of this species in 1999, the earliest fossil evidence known for a flat-faced early human, a significant shift in skull structure, was around 2 million years ago.

Australopithecus africanus

Au. africanus was anatomically similar to Au. afarensis, with a combination of human-like and ape-like features. Compared to Au. afarensis, Au. africanus had a rounder cranium housing a larger brain and smaller teeth, but it also had some ape-like features including relatively long arms and a strongly sloping face that juts out from underneath the braincase with a pronounced jaw. Like Au. afarensis, the pelvis, femur (upper leg), and foot bones of Au. africanus indicate that it walked bipedally, but its shoulder and hand bones indicate they were also adapted for climbing.

Paranthropus aethiopicus

Paranthropus aethiopicus is still much of a mystery to paleoanthropologists, as very few remains of this species have been found. The discovery of the 2.5 million year old ’Black Skull’ in 1985 helped define this species as the earliest known robust australopithecine. P. aethiopicus has a strongly protruding face, large megadont teeth, a powerful jaw, and a well-developed sagittal crest on top of skull, indicating huge chewing muscles, with a strong emphasis on the muscles that connected toward the back of the crest and created strong chewing forces on the front teeth.

Australopithecus garhi

This species is not well documented; it is defined on the basis of one fossil cranium and four other skull fragments, although a partial skeleton found nearby, from about the same layer, is usually included as part of the Australopithecus garhi sample. The associated fragmentary skeleton indicates a longer femur (compared to other Australopithecus specimens, like ‘Lucy’) even though long, powerful arms were maintained. This suggests a change toward longer strides during bipedal walking.

Homo habilis

This species, one of the earliest members of the genus Homo, has a slightly larger braincase and smaller face and teeth than in Australopithecus or older hominin species. But it still retains some ape-like features, including long arms and a moderately-prognathic face. Its name, which means ‘handy man’, was given in 1964 because this species was thought to represent the first maker of stone tools. Currently, the oldest stone tools are dated slightly older than the oldest evidence of the genus Homo.

Paranthropus boisei

Like other members of the Paranthropus genus, P. boisei is characterized by a specialized skull with adaptations for heavy chewing. A strong sagittal crest on the midline of the top of the skull anchored the temporalis muscles (large chewing muscles) from the top and side of the braincase to the lower jaw, and thus moved the massive jaw up and down. The force was focused on the large cheek teeth (molars and premolars). Flaring cheekbones gave P. boisei a very wide and dish-shaped face, creating a larger opening for bigger jaw muscles to pass through and support massive cheek teeth four times the size of a modern human’s. This species had even larger cheek teeth than P. robustus, a flatter, bigger-brained skull than P. aethiopicus, and the thickest dental enamel of any known early human. Cranial capacity in this species suggests a slight rise in brain size (about 100 cc in 1 million years) independent of brain enlargement in the genus Homo.

Australopithecus sediba

The fossil skeletons of Au. sediba from Malapa cave are so complete that scientists can see what entire skeletons looked like near the time when Homo evolved. Details of the teeth, the length of the arms and legs, and the narrow upper chest resemble earlier Australopithecus, while other tooth traits and the broad lower chest resemble humans. These links indicate that Au. Functional changes in the pelvis of Au. sediba point to the evolution of upright walking, while other parts of the skeleton retain features found in other australopithecines. Measurements of the strength of the humerus and femur show that Au. sediba had a more human-like pattern of locomotion than a fossil attributed to Homo habilis. These features suggest that Au. sediba walked upright on a regular basis and that changes in the pelvis occurred before other changes in the body that are found in later specimens of Homo. The Australopithecus sediba skull has several derived features, such as relatively small premolars and molars, and facial features that are more similar to those in Homo. However, despite these changes in the pelvis and skull, other parts of Au. sediba skeleton shows a body similar to that of other australopithecines with long upper limbs and a small cranial capacity. The fossils also show that changes in the pelvis and the dentition occurred before changes in limb proportions or cranial capacity.

Homo rudolfensis

There is only one really good fossil of this Homo rudolfensis: KNM-ER 1470, from Koobi Fora in the Lake Turkana basin, Kenya. It has one really critical feature: a braincase size of 775 cubic centimeters, which is considerably above the upper end of H. habilis braincase size. At least one other braincase from the same region also shows such a large cranial capacity. Originally considered to be H. habilis, the ways in which H. rudolfensis differs is in its larger braincase, longer face, and larger molar and premolar teeth. Due to the last two features, though, some scientists still wonder whether this species might better be considered an Australopithecus, although one with a large brain!

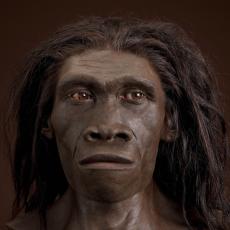

Homo erectus

Early African Homo erectus fossils (sometimes called Homo ergaster) are the oldest known early humans to have possessed modern human-like body proportions with relatively elongated legs and shorter arms compared to the size of the torso. These features are considered adaptations to a life lived on the ground, indicating the loss of earlier tree-climbing adaptations, with the ability to walk and possibly run long distances. Compared with earlier fossil humans, note the expanded braincase relative to the size of the face. The most complete fossil individual of this species is known as the ‘Turkana Boy’ – a well-preserved skeleton (though minus almost all the hand and foot bones), dated around 1.6 million years old. Microscopic study of the teeth indicates that he grew up at a growth rate similar to that of a great ape. There is fossil evidence that this species cared for old and weak individuals. The appearance of Homo erectus in the fossil record is often associated with the earliest handaxes, the first major innovation in stone tool technology.

Paranthropus robustus

Paranthropus robustus is an example of a robust australopithecine; they had very large megadont cheek teeth with thick enamel and focused their chewing in the back of the jaw. Large zygomatic arches (cheek bones) allowed the passage of large chewing muscles to the jaw and gave P. robustus individuals their characteristically wide, dish-shaped face. A large sagittal crest provided a large area to anchor these chewing muscles to the skull. These adaptations provided P. robustus with the ability of grinding down tough, fibrous foods. It is now known that ‘robust’ refers solely to tooth and face size, not to the body size of P. robustus.

Homo heidelbergensis

This early human species had a very large browridge, and a larger braincase and flatter face than older early human species. It was the first early human species to live in colder climates; their short, wide bodies were likely an adaptation to conserving heat. It lived at the time of the oldest definite control of fire and use of wooden spears, and it was the first early human species to routinely hunt large animals. This early human also broke new ground; it was the first species to build shelters, creating simple dwellings out of wood and rock.

Homo floresiensis

Remains of one of the most recently discovered early human species, Homo floresiensis (nicknamed ‘Hobbit’), have so far only been found on the Island of Flores, Indonesia. The fossils of H. floresiensis date to between about 100,000 and 60,000 years ago, and stone tools made by this species date to between about 190,000 and 50,000 years old. H. floresiensis individuals stood approximately 3 feet 6 inches tall, had tiny brains, large teeth for their small size, shrugged-forward shoulders, no chins, receding foreheads, and relatively large feet due to their short legs. Despite their small body and brain size, H. floresiensis made and used stone tools, hunted small elephants and large rodents, coped with predators such as giant Komodo dragons, and may have used fire.

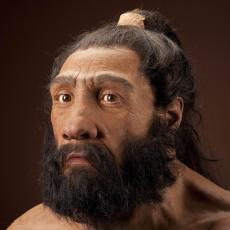

Homo neanderthalensis

Neanderthals are our closest extinct human relative. Some defining features of their skulls include the large middle part of the face, angled cheek bones, and a huge nose for humidifying and warming cold, dry air. Their bodies were shorter and stockier than ours, another adaptation to living in cold environments. But their brains were just as large as ours and often larger - proportional to their brawnier bodies.Neanderthals made and used a diverse set of sophisticated tools, controlled fire, lived in shelters, made and wore clothing, were skilled hunters of large animals and also ate plant foods, and occasionally made symbolic or ornamental objects. There is evidence that Neanderthals deliberately buried their dead and occasionally even marked their graves with offerings, such as flowers. No other primates, and no earlier human species, had ever practiced this sophisticated and symbolic behavior.

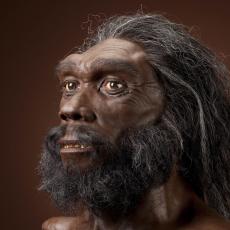

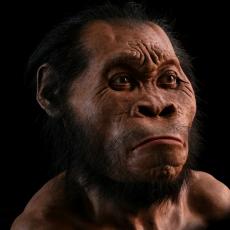

Homo naledi

Fossil hominins were first discovered in the Dinaledi Chamber of the Rising Star Cave system in South Africa during an expedition led by Lee Berger beginning October 2013. In November 2013 and March 2014, over 1550 specimens from at least 15 Homo naledi individuals were recovered from this site. This excavation remains the largest collection of a single hominin species that has been found in Africa. Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker found an additional 133 Homo naledi specimens in the nearby Lesedi Chamber in 2013, representing at least another 3 individuals – two adults and a juvenile. In 2017, the Homo naledi fossils were dated to between 335,000 and 236,000 years ago.

Homo sapiens

The species that you and all other living human beings on this planet belong to is Homo sapiens. During a time of dramatic climate change 300,000 years ago, Homo sapiens evolved in Africa. Like other early humans that were living at this time, they gathered and hunted food, and evolved behaviors that helped them respond to the challenges of survival in unstable environments.Anatomically, modern humans can generally be characterized by the lighter build of their skeletons compared to earlier humans. Modern humans have very large brains, which vary in size from population to population and between males and females, but the average size is approximately 1300 cubic centimeters. Housing this big brain involved the reorganization of the skull into what is thought of as "modern" -- a thin-walled, high vaulted skull with a flat and near vertical forehead. Modern human faces also show much less (if any) of the heavy brow ridges and prognathism of other early humans. Our jaws are also less heavily developed, with smaller teeth.